The Nathan Hale Schoolhouse: a travelogue

As landmark reaches its 250th anniversary, a look back at its endless journey

Editor’s note: This story was drawn primarily from the archives of The Day. Click links in the text to see original stories.

When Connecticut celebrated its 300th birthday in 1935, New London was represented in a parade by a 12-foot-long replica of the Nathan Hale Schoolhouse.

It was on wheels.

Most of what makes that funny hadn’t happened yet, but in later years, the sight of the building rolling down the street wasn’t exactly rare.

Throughout the spectacle of its many moves, the gambrel-roofed landmark has survived, first by chance, then by design, and finally in defiance of New London’s refusal to just leave it alone. Now enjoying a well-deserved rest at its seventh location, the schoolhouse has become a punchline reflecting the zaniness of life in New London.

It also continues to serve its primary purpose, sustaining the memory of Hale. The future hero was hired to teach there 250 years ago this month.

To mark the anniversary, here are the travels and travails of a building that couldn’t sit still.

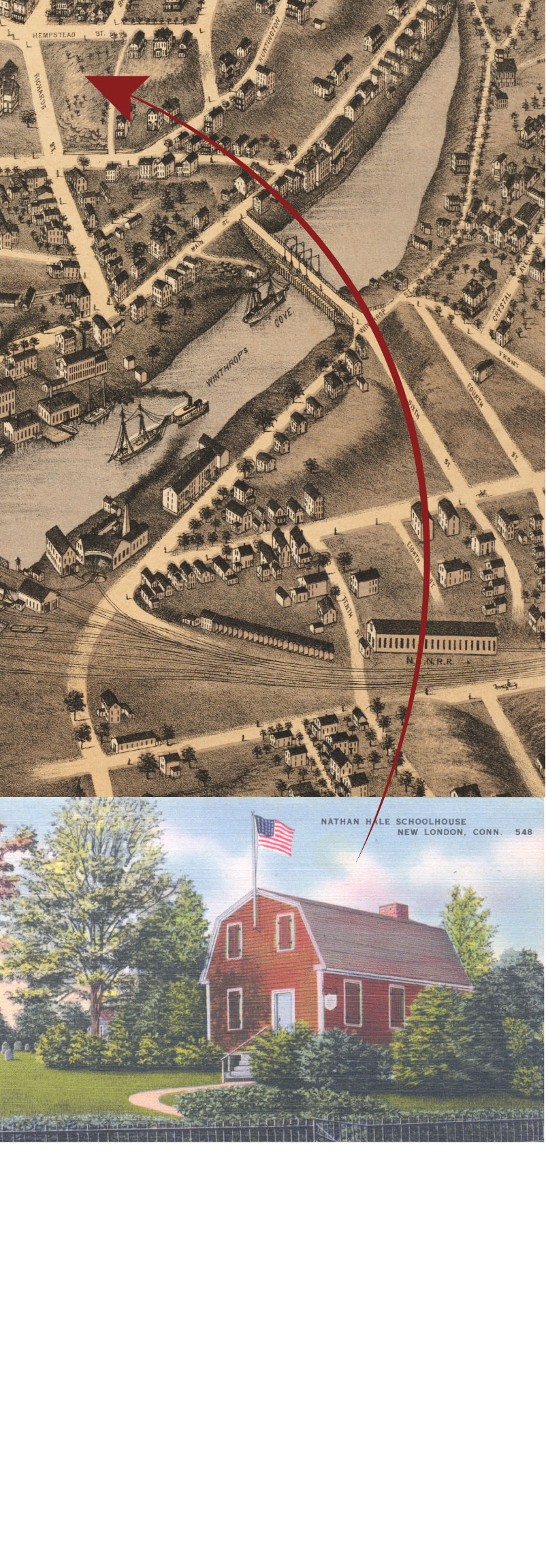

Stop 1: State Street

“Commodious” was how the schoolhouse was described in 1774, just after it was built as a private institution called Union School. The building went up on what’s now State Street where the Crocker House is. An English education and classical preparation for college were to be offered.

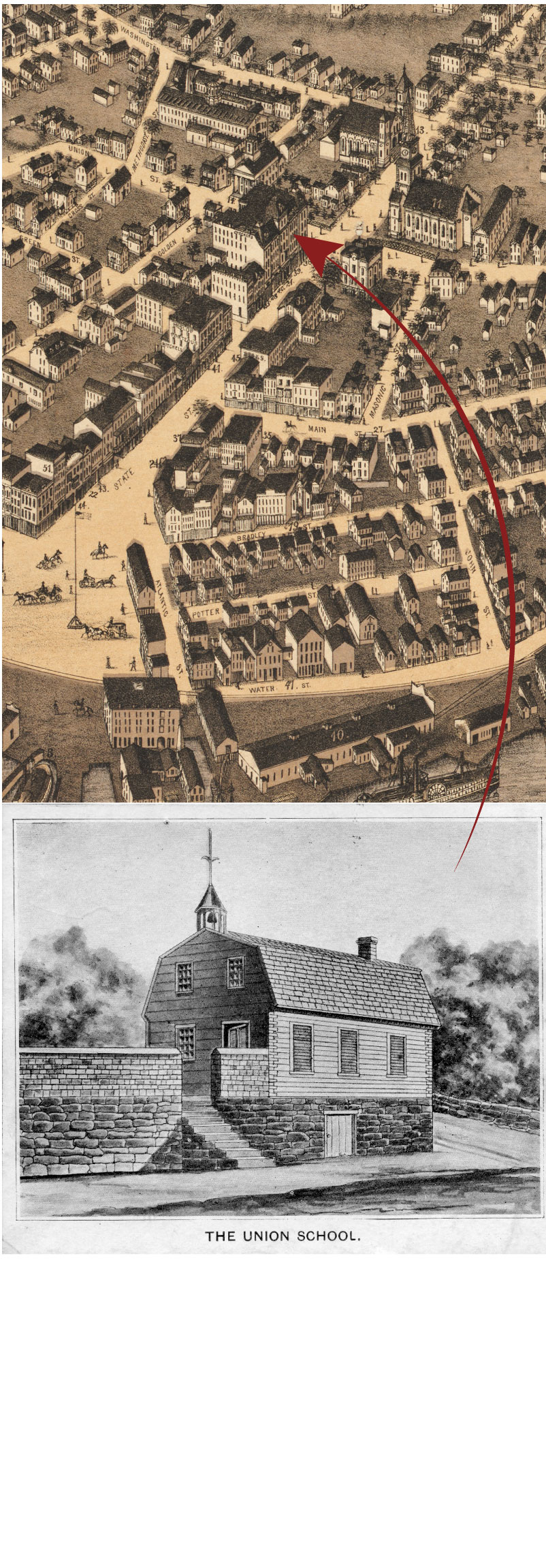

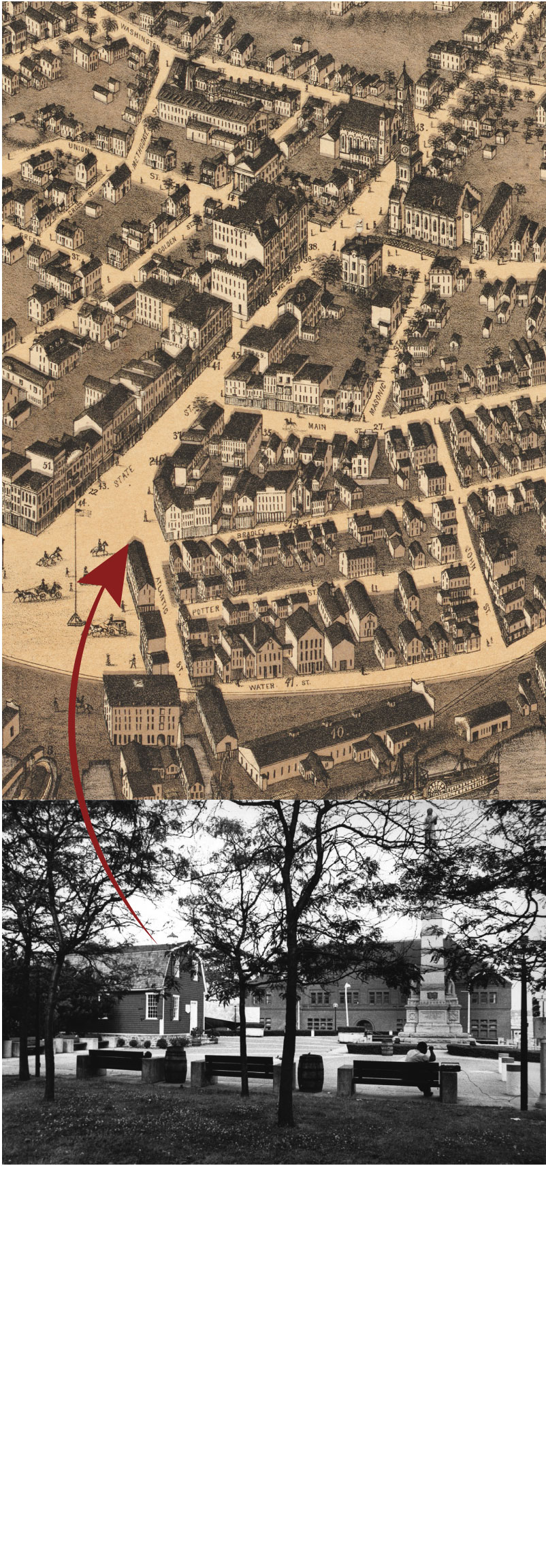

Nathan Hale was hired in 1774 to teach at New London’s newly built Union School on State Street, where the Crocker House now stands. This 1876 bird’s-eye view map was drawn by O.H. Bailey & Co. of Boston.

Building image courtesy New London Public Library

Nathan Hale was hired in 1774 to teach at New London’s newly built Union School on State Street, where the Crocker House now stands. This 1876 bird’s-eye view map was drawn by O.H. Bailey & Co. of Boston.

Building image courtesy New London Public Library

The proprietors’ petition for incorporation caught the attention of Hale, a recent Yale graduate then teaching in East Haddam. He was hired in March 1774 and took charge of a class of 32 boys. He also taught 20 girls from 5 to 7 a.m.

By all accounts he was popular, both with students and the school’s administrators.

“They are desirous that I would continue and settle in the school, and propose a considerable increase of wages,” he wrote his uncle. “I am much at a loss whether to accept their proposals.”

The outbreak of the Revolution in 1775 settled the matter, and Hale resigned to join the war. He was soon hanged as a spy by the British, after his famous last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

The school continued with other instructors and survived the burning of New London in 1781. When a new home for the institution was built in the early 19th century, the building’s time as a schoolhouse ended.

But its many moves still lay ahead.

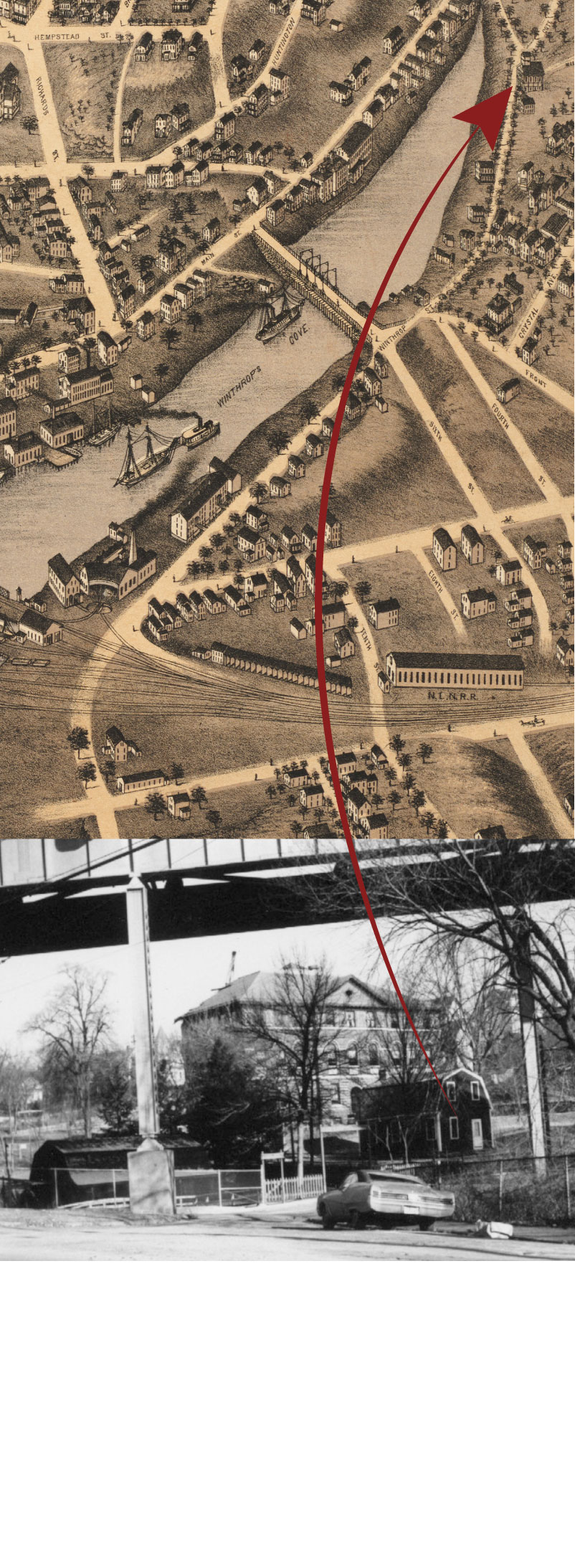

Stop 2: Union Street

Taking its name from the school, Union Street opened in 1786. Its creation put the building on a corner lot and laid the path for its first journey. Around 1832, it was moved down the street to become a residence.

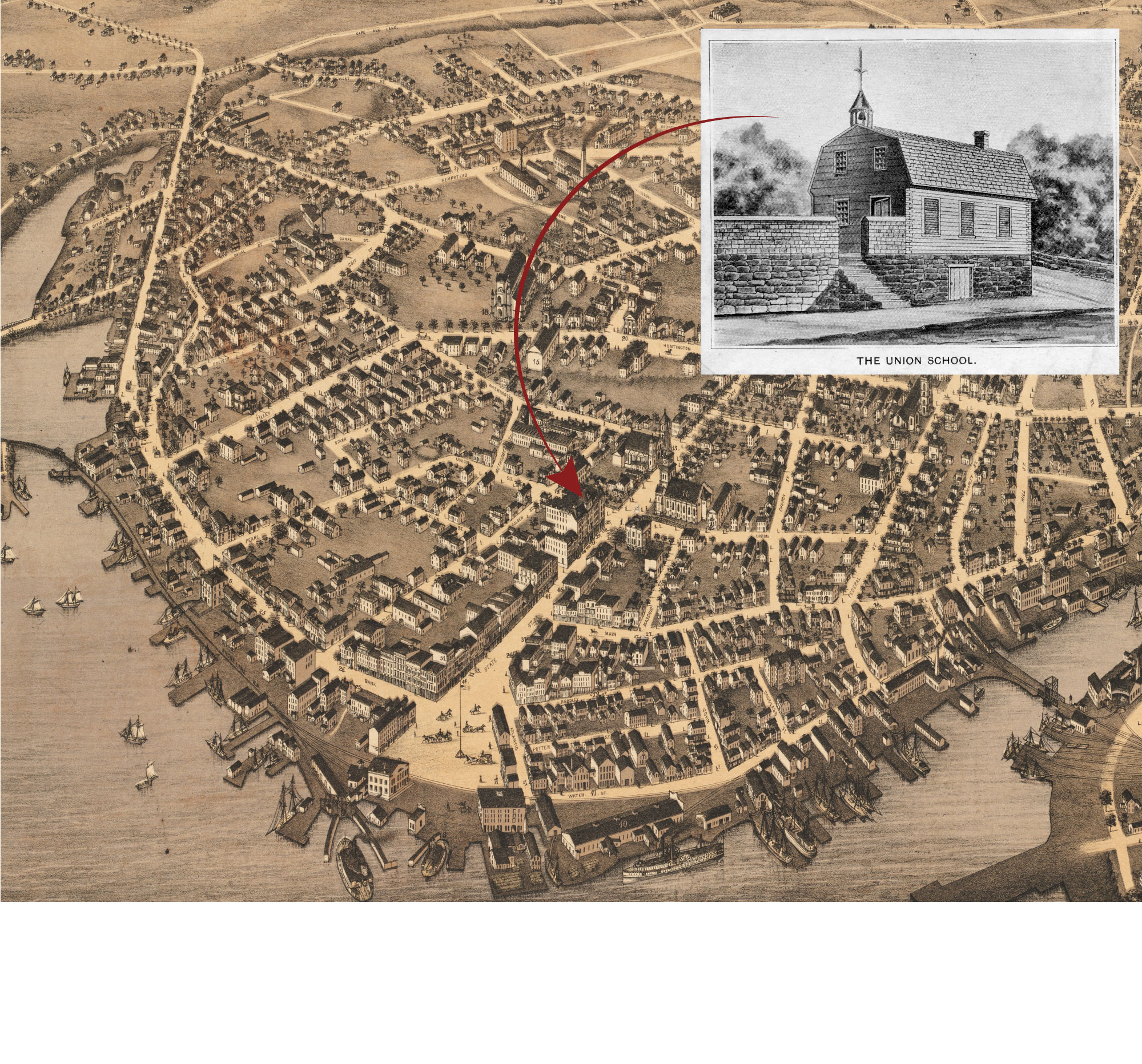

Around 1832, the schoolhouse was moved a short distance down Union Street to become a residence. The building began to fade into obscurity.

Building photo courtesy New London Public Library

Around 1832, the schoolhouse was moved a short distance down Union Street to become a residence. The building began to fade into obscurity.

Building photo courtesy New London Public Library

The place wasn’t called Union School anymore, but its days as a seat of learning weren’t over. At least two women who lived there at different times taught from home. The last, around 1849, was known as Granny Pease.

“She had a dreadful temper and when out of sorts would thrash the boys as good as a man could do it,” The Day’s R.B. Wall wrote.

Pease also managed to set the place on fire once while fumigating it against smallpox. Another brush with fire came in 1853, when the piano factory next door burned to the ground.

The house’s surroundings changed further with the expansion of a nearby foundry. In later years, a four-story brick building towered over it.

During that time, the house faded into obscurity, its early history apparently forgotten. Consider this sentence, presented as an isolated factoid in the New London Evening Telegram in 1880:

“The old building opposite the Second Baptist church on Union street, adjoining the entrance to Wilson’s foundry, was once the school-house of Nathan Hale.”

It sounded as if this was something most New Londoners didn’t know.

Stop 3: Burial ground

Hale himself had gone unremembered for a time. An 1856 biography opened with a lament from Stephen Hempstead, his friend from New London.

“I do think it hard,” Hempstead said, “that Hale, who was equally brave, young, accomplished, learned and honorable — should be forgotten on the very threshold of his fame.”

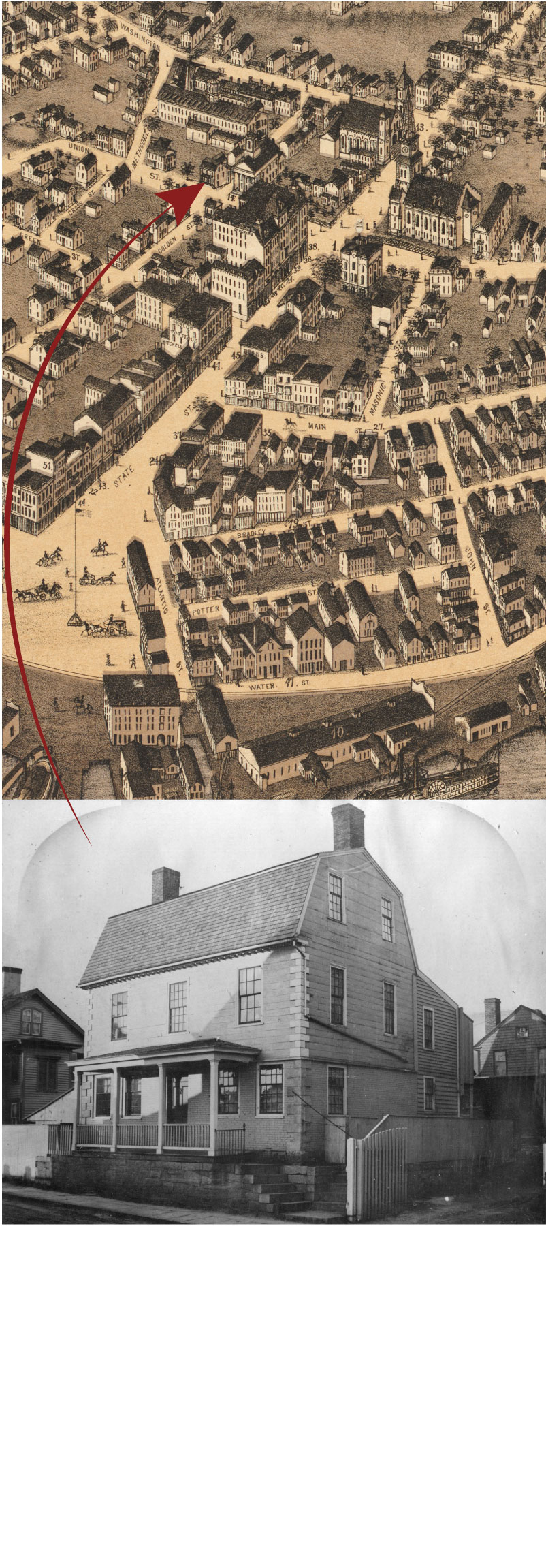

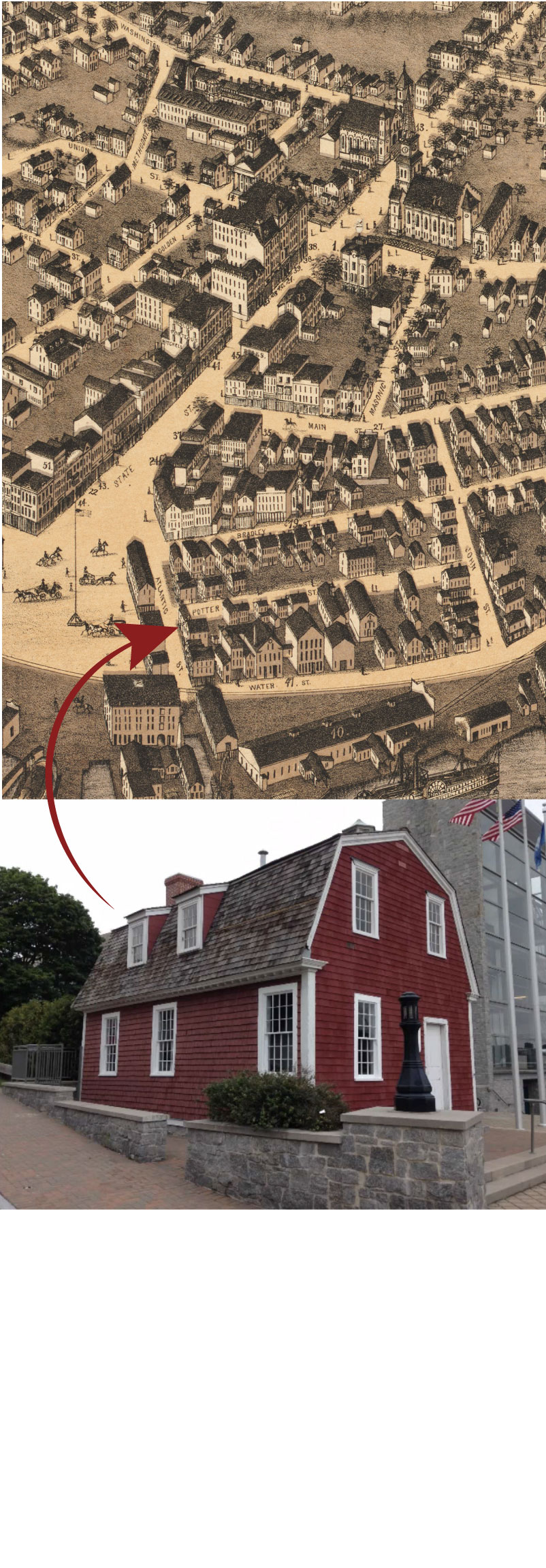

The Connecticut Society of the Sons of American Revolution rediscovered Hale’s schoolhouse in 1891 as interest in Hale was undergong a revival. SAR eventually raised enough money to buy the building, which was moved to the Antientest Burial Ground.

Building photo courtesy John Ruddy

The Connecticut Society of the Sons of American Revolution rediscovered Hale’s schoolhouse in 1891 as interest in Hale was undergong a revival. SAR eventually raised enough money to buy the building, which was moved to the Antientest Burial Ground.

Building photo courtesy John Ruddy

But a revival of interest nationally led New London to rediscover him. In 1891, a street, a tugboat and a fraternal order were named for him, as was Nathan Hale Grammar School on Williams Street.

The same year, the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution found Hale’s schoolhouse, altered but intact, in the shadow of the foundry, by then a quilt factory. It was the home of the superintendent, but the SAR hoped to buy and restore the building.

“The advice of those best informed upon the subject was to wait — and we waited, with intervals of discussion and re-investigation, for eight years,” SAR President Jonathan Trumbull recalled.

By 1899 the purchase still seemed so unlikely that the superintendent added a second-floor balcony to his home. But the SAR raised funds and eventually had enough to complete the purchase.

The school had to be moved, and the city considered several sites, including Williams Memorial Park and Nathan Hale Grammar School. But officials settled on the Antientest Burial Ground, a place full of history.

In April 1901 the balcony and other additions were stripped off, and the building went on the road for the second time, moving through Union and Federal streets over several days until it reached the cemetery, where a new foundation awaited.

The restored schoolhouse was dedicated with a parade and speeches. It had emerged from obscurity to become a monument, apparently reaching its final destination.

That wasn’t true by a long shot.

Stop 4: Old Town Mill

The idea of moving the schoolhouse again arose from the tribulations of another landmark. In 1960 the Old Town Mill was neglected and in disrepair when the City Council learned of a plan to restore it. But there was a catch. The mill would be moved to Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts.

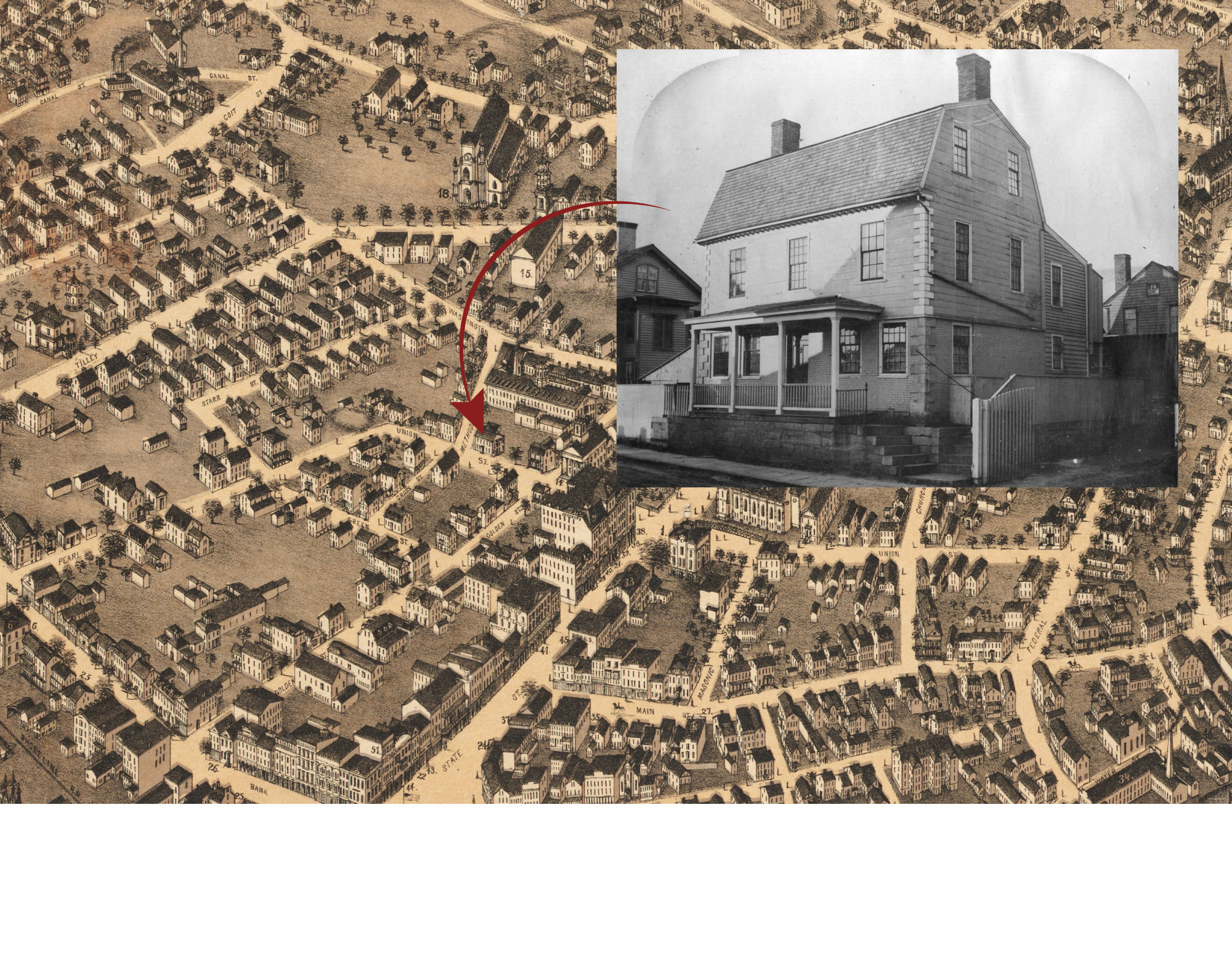

In 1966, a wrecker spent several days towing the schoolhouse to the Old Town Mill. At this point, both structures were neglected and in disrepair.

Building photo courtesy John Ruddy

iN 1966, a wrecker spent several days towing the schoolhouse to the Old Town Mill. At this point, both structures were neglected and in disrepair.

Building photo courtesy John Ruddy

A study committee proposed an alternative: Fix it where it was and move the schoolhouse next door to attract visitors. The SAR liked the idea but wanted a different location: Ocean Beach Park. That didn’t sit well with everyone.

“The announcement of a plan to remove Plymouth Rock could not have startled me more,” wrote Dwight Lyman of the New London County Historical Society.

Neglect and vandalism also shadowed the schoolhouse, and a few years later the stalled plan to move it was revived. In May 1966 a wrecker towed the building to the mill over several days. It spent one night parked in a no-parking zone on Richards Street.

The two ancient buildings were finally together under the Gold Star Memorial Bridge. There was just one problem: A second bridge was planned, and construction would come so close that nearby Winthrop School had to be demolished.

The building’s future looked ominous.

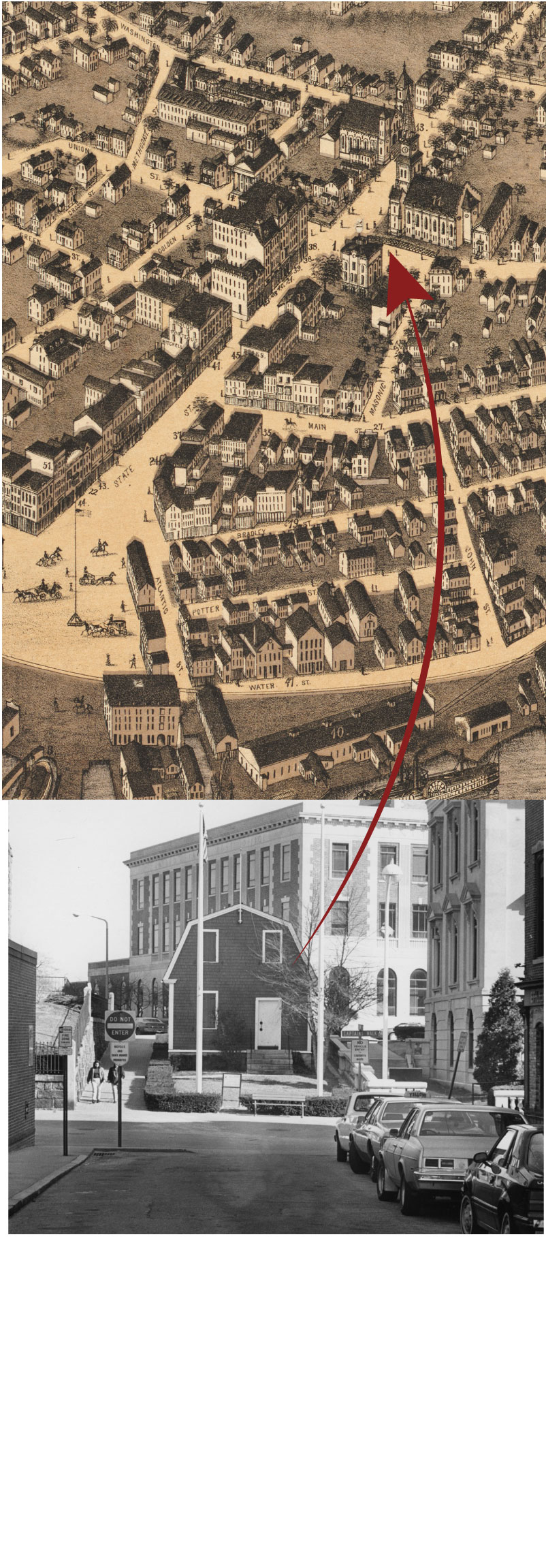

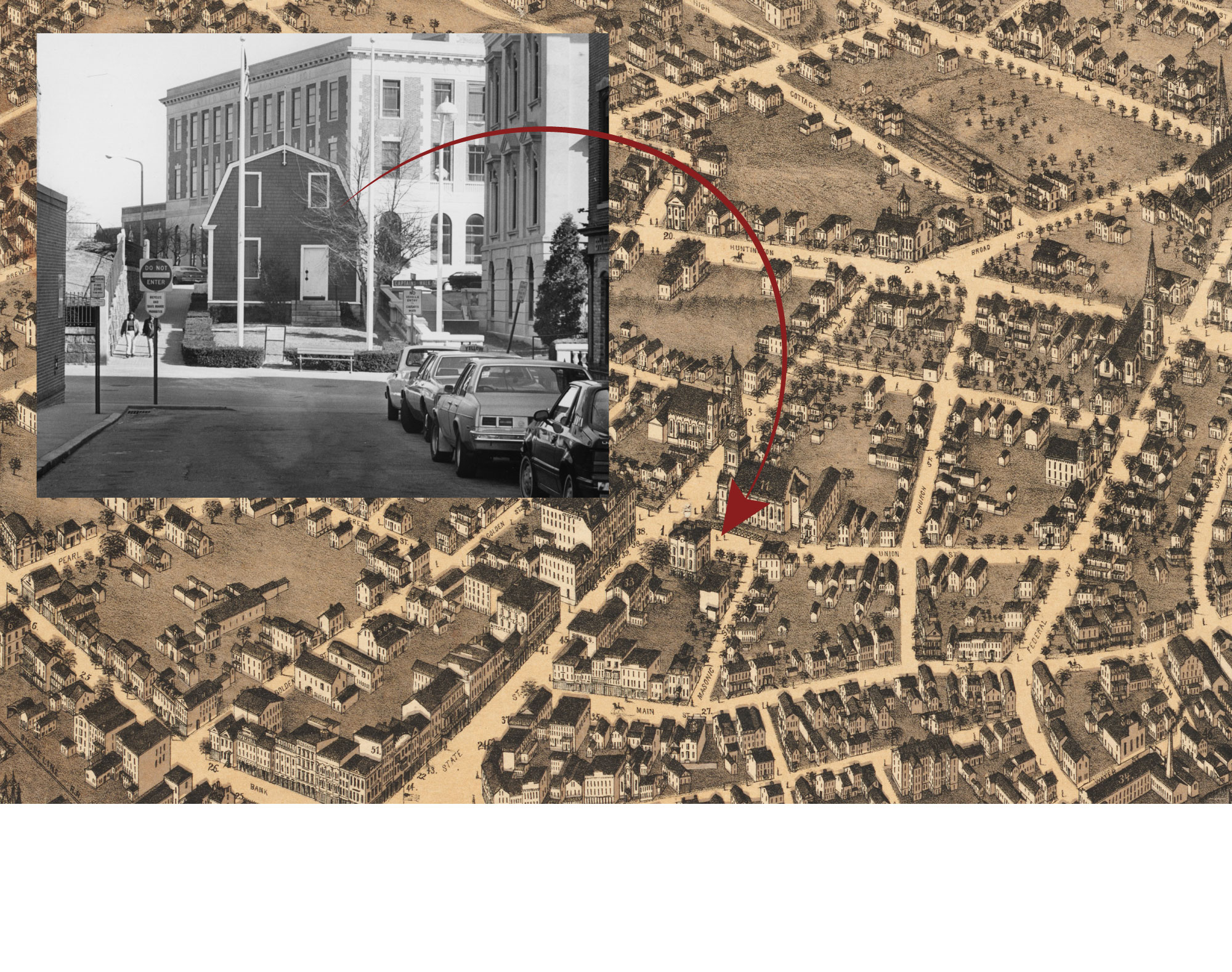

Stop 5: Captain’s Walk

The schoolhouse survived the new bridge but languished beneath it. By 1974 there was a consensus to move it back downtown, but no one could agree where. The likeliest spot was next to City Hall in the middle of Union Street, which had been left a dead end when State Street became a pedestrian mall called Captain’s Walk.

In 1975, the building arrived next to City Hall on Union Street, which had become a dead end when State Street became a pedestrian mall.

Building photo: The Day

The schoolhouse languished at its site beneath the new span and talk turned to moving it back downtown. In 1976, the building arrived next to City Hall on Union Street, which had become a dead end when State Street became a pedestrian mall.

Building photo: The Day

Downtown merchants hated the idea and threatened to sue. The Day condemned the city’s indecisiveness, editorializing that Hale “would quake with indignation” if he could witness it.

The city dismissed the merchants’ objections, and in April 1975, the schoolhouse arrived on Union Street near its original location, having passed its former home at the burial ground on the trip back.

Barely two years later, the city decided it might be a good idea to reopen Union Street to traffic, which would mean another move. The idea was considered, rejected, considered again and dropped.

Then, in 1980, the City Council did a larger study of downtown traffic, which had been snarled by Captain’s Walk. Moving the schoolhouse was back on the table.

A letter to The Day suggested Hale’s spirit was suffering from “motion sickness.”

Stop 6: Parade

While the city dithered, the SAR, the building’s fed-up owner, took matters into its own hands. In 1985 the group’s board voted to move it to Mitchell College, whose president, Robert Weller, was a Hale buff. There was already a statue on campus.

City officials were dismayed but powerless.

“We opened up a can of worms, and now we may have lost it,” Mayor Carmelina Kanzler said.

After years of bickering, the schoolhouse found itself in yet another location in 1988, near the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. The move was supposed to be its last.

Building photo: The Day

After years of bickering, the schoolhouse found itself in yet another location in 1988, near the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. The move was supposed to be its last.

Building photo: The Day

Mitchell took ownership with the stipulation that the building be moved within nine months. But the deal was scrapped amid an outcry, and the SAR took it back.

Two years later, the City Council, relieved the building hadn't moved to Mitchell, finally voted to reopen Union Street, forcing it to move somewhere else.

But where? The SAR and most city officials wanted to send it to the Parade, but the council instead voted to put it in Williams Park, where there was another statue of Hale. Faced with the SAR’s fury, councilors changed their mind.

In September 1988, after a short trip, the schoolhouse found itself near the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Earlier that year, the SAR had vowed that wherever it ended up, the move would be its last.

Not quite.

Stop 7: Atlantic Street

Giggles rippled through the crowd at the Radisson Hotel as a design team recommended post-Captain’s Walk changes to New London. A reworked Parade would be the heart of downtown, and there was no place on it for the Nathan Hale Schoolhouse. It was April 1989, seven months after the most recent move.

“I think the people of New London are probably ready to shoot whoever votes for this,” SAR President Stanley Eno said. “The building hasn’t even been rededicated.”

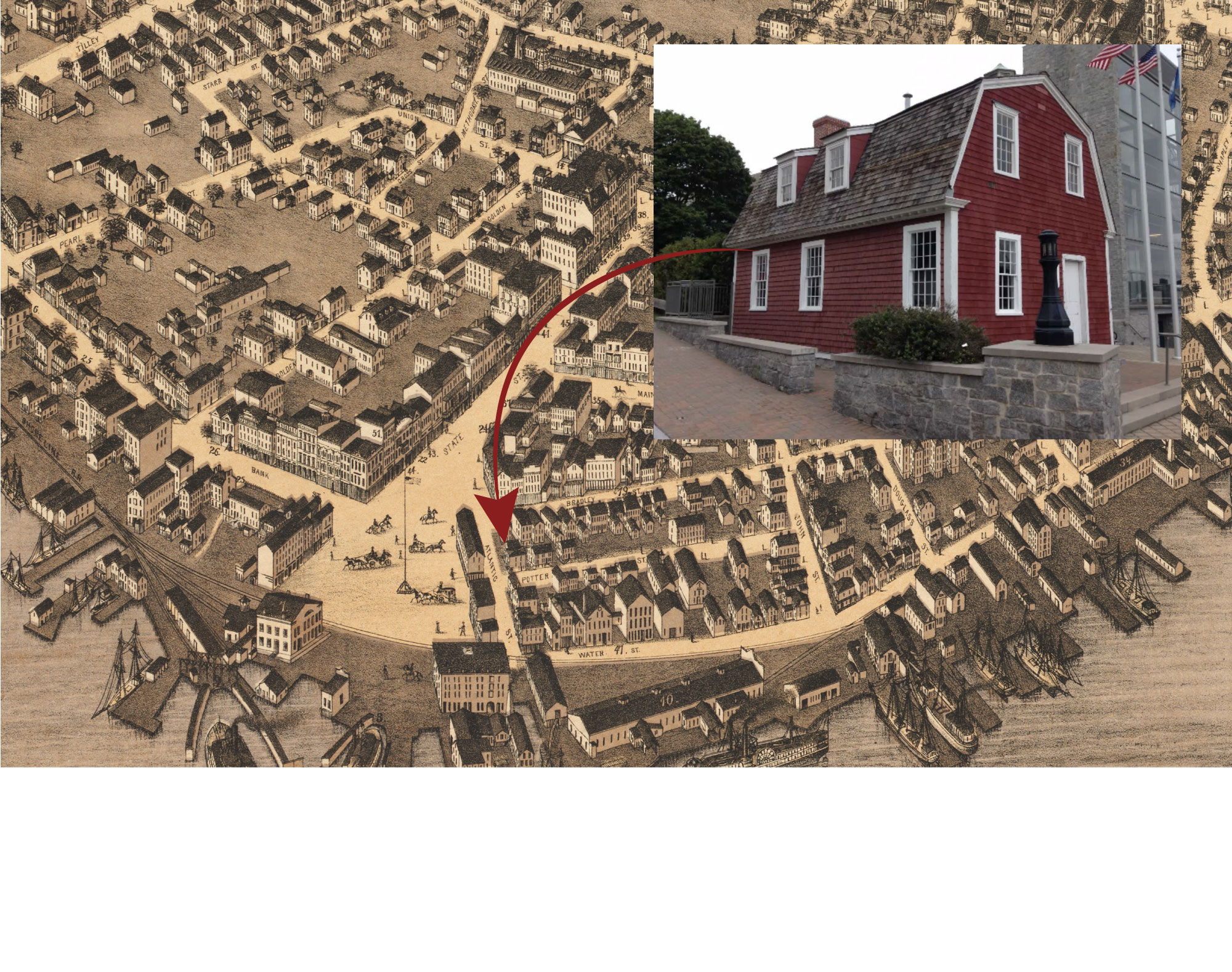

On-again, off-again plans to rework the Parade at the heart of downtown resurfaced in 2007. The schoolhouse would have to move one more time, about 100 feet to Atlantic Street near the Water Street Parking Garage.

Building photo: The Day

On-again, off-again plans to rework the Parade at the heart of downtown resurfaced in 2007. The schoolhouse would have to move one more time, about 100 feet to Atlantic Street near the Water Street Parking Garage.

Building photo: The Day

The council approved the plan anyway, which prompted the Antiquarian and Landmarks Society to offer the building a refuge from city officials at the Hempsted Houses.

That was unnecessary, as the Parade plan fell through. But in 1996, the SAR again entertained the idea of moving the building on its own and reconsidered both the Mitchell and Hempsted options. Its foundation was crumbling, threatening the rest of the structure. That plan also went nowhere.

The Parade redesign resurfaced in 2007, and this time it was destined to happen. The schoolhouse would have to move one more time, but it would be a quick trip, about 100 feet to Atlantic Street near the Water Street parking garage. Even the SAR went along with the idea.

In January 2009 the schoolhouse crossed the street, its shortest move ever, to the spot where it has sat, unmolested, ever since.

Later, The Day editorialized approvingly about the new-look Parade.

“Nearby,” it said, "the historic Nathan Hale Schoolhouse has been moved — this time we believe for the last time.”

We’ll see.

j.ruddy@theday.com

The butt of a thousand jokes

There were plenty of good ones about the Nathan Hale Schoolhouse as it moved endlessly around town. A sample from the pages of The Day:

“Finally comes a suggestion from Groton that the schoolhouse be lifted by helicopter and deposited at a suitable spot in the Fort Griswold restoration.”

— Editorial, Nov. 9, 1974

“Nathan Hale was fortunate, I suppose, to be hanged once and done with it.”

— Steven Slosberg, columnist, Feb. 26, 1986

“It makes more moves than a Navy family.”

— Editorial, March 22, 1986

“Oh! My aching timbers. I’m going to have my body jacked up once again, to get still another view of New London. … My wood frame is certainly feeling the strain.”

— Letter to the editor, April 17, 1986

“I took a walk up Captain’s Walk … to make sure the Nathan Hale Schoolhouse was still there. You never know.”

— John Foley, columnist, April 30, 1986

“This building has the distinction of being the country’s oldest mobile home.”

— Melvin Jetmore, public works director, Sept. 26, 1988

“I am sure Nathan Hale regrets that he had but one schoolhouse to leave to New London.”

— Letter to the editor, Aug. 11, 1989

“If Nathan Hale came back for a visit and asked directions to his old schoolhouse I don’t know how many New Londoners could tell him where it is at the moment.”

— Letter to the editor, July 26, 1990

Comment threads are monitored for 48 hours after publication and then closed.